Most Aussies have heard of Norfolk Island, but don’t know much about it. The more I learnt about it, the more curious I became about its unique sub-culture and history. Here’s a snapshot based on my five days there in September.

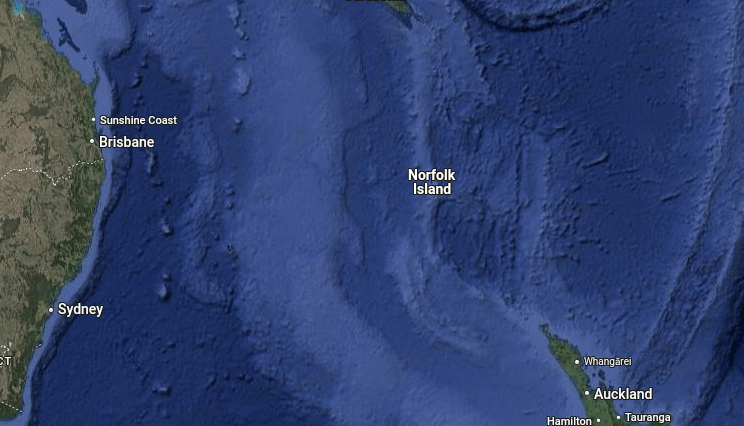

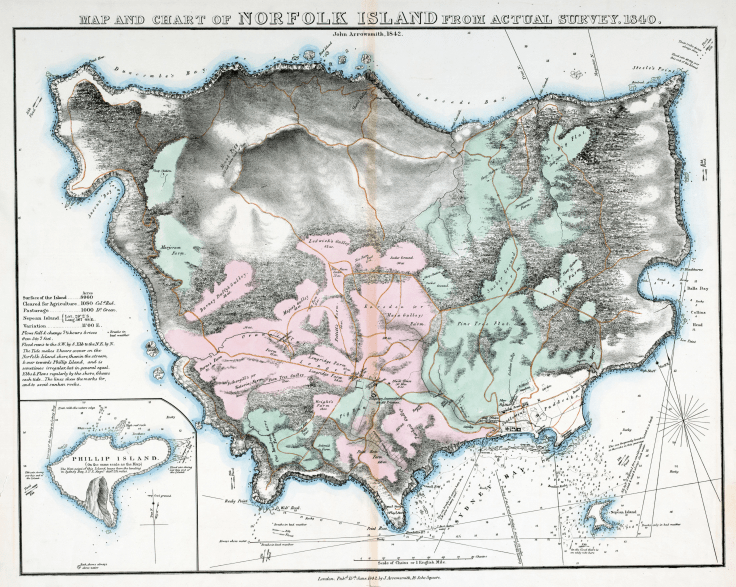

The island is halfway between Brisbane and Auckland at about the same latitude as Byron Bay with a very pleasant climate. It’s approximately 34.6 km2, very green and has a population of 2,188 (2021 census). Norfolk Pine trees are a species native to the island and an iconic symbol. (Map)

When they are young, they have a distinctive Christmas tree appearance. They are dotted all over the island, which was once covered in rain forest. Two related species can be seen growing in Australia. Sixty percent of the flora is now non-native species. There are no snakes, possums, leaches or tics, and very few mosquitoes. Kingston, the capital.

Half the residents can trace their ancestry to the Pitcairn Islanders; descendants of Tahitians and Englishmen who mutinied on the HMS Bounty in 1789. The most important local holiday is Bounty Day, celebrated on 8 June, in memory of the arrival of the Pitcairn Islanders in 1856. (Wikipedia)

A brief history of human habitation

Polynesians

900 years ago Polynesians settled on the southern coast, but left after a few hundred years. Several hundred years later, Captain James Cook landed at the same spot (Emily Bay) and sketched this pine tree that still grows there.

He thought the trees would make good masts.

First Settlement

Unfortunately, they didn’t, but there was flax growing (useful for rigging and sails) and it (along with concern that the French would move in) spurred the British government to order the Commodore of the First Fleet to Australia, Arthur Phillip, to establish a settlement there soon after founding Sydney Town at Port Jackson, New South Wales in 1788. The south coast proved to be the best landing spot.

More than a year later (28th April, 1789), William Bligh, captain of the HMS Bounty, was cast adrift by the mutineers in a small long boat near present day Tonga. Interestingly, he headed for an established colony on Timor more than twice the distance to Sydney. The First Fleet left England six months before the Bounty, so Bligh would have known it had arrived in Botany Bay. Was this an error of judgement, or a calculated decision?

The Siruis was the flagship of the First Fleet and one of only two (out of eleven) left to serve the new colonies (the rest sailed away). It was used to colonize Norfolk Island, but two years later was wrecked there at Slaughter Bay, known at the time as Sydney Bay. It was a great loss to Sydney Town (NSW) which was close to starving.

In six years, the population reached 1,000 and although its excess produce sometimes supplied Sydney, ten years later it was deemed too remote and costly. It was abandoned and everything burnt and destroyed to prevent another European power getting a foothold.

Penal Settlement

Another fifteen years later the island’s remoteness was viewed as advantageous for a penal colony for the worst convicts (repeat offenders). This time, more permanent stone buildings were built, many of which remain.

Moreton Bay Penal Settlement (Brisbane) was founded at the same time for similar reasons and both were very harsh places. Both also reached their use-by date in the late 1840s and were temporarily closed. Brisbane was soon opened to free settlement.

Third Settlement – Pitcairn Islanders

By this time – 1856 – the population on Pitcairn Island had grown such that they pleaded to Queen Victoria, who approved the migration of all 193 of them to Norfolk. They brought with them their unique language and culture. I did an Island Culture Tour and learnt that the language is a mix of Tahitian and 18th Century English, with a vocabulary of about 600 words.

Traditional weaving, dancing and customs such as free, volunteer-run funerals and burials are still celebrated among the descendants.

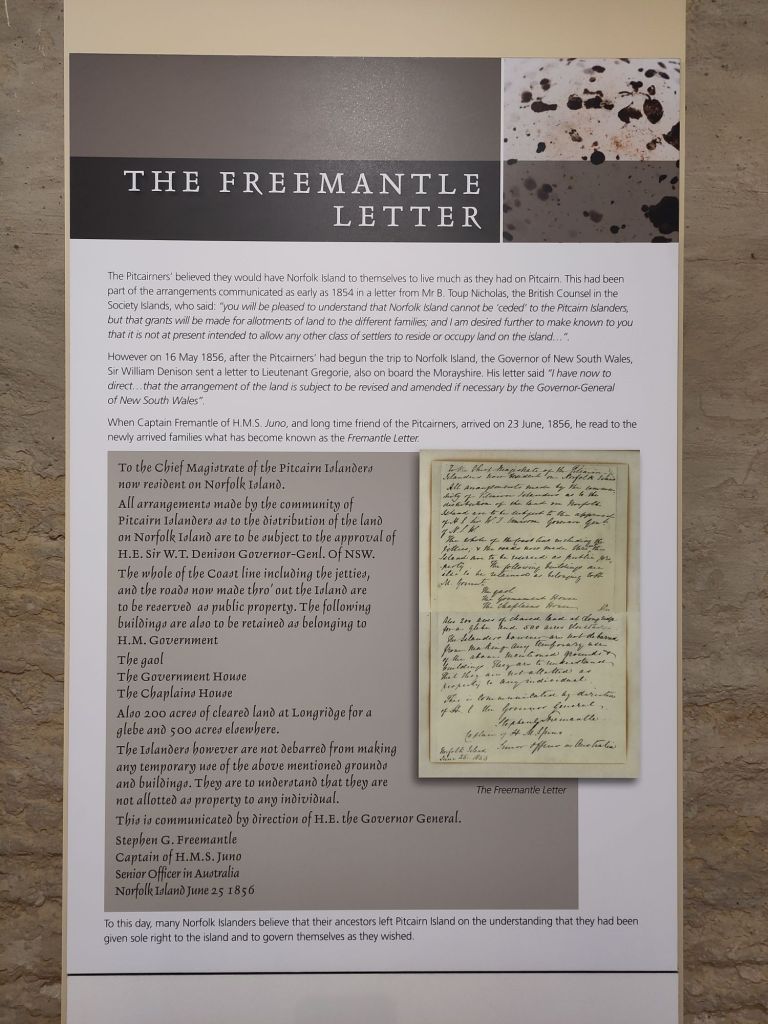

To this day the descendants claim they were promised the whole island as sovereign land. However, it seems the conditions where changed while they were en route to Norfolk and the issue has been contentious ever since.

Some went back to Pitcairn where now 40 of them are, according to a local Pitcairn descended hat-maker, supported by both Britain and the EU to the tune of $41 million per year! They are a draw-card to cruise ships to whom they sell their wares.

Melanesian Mission

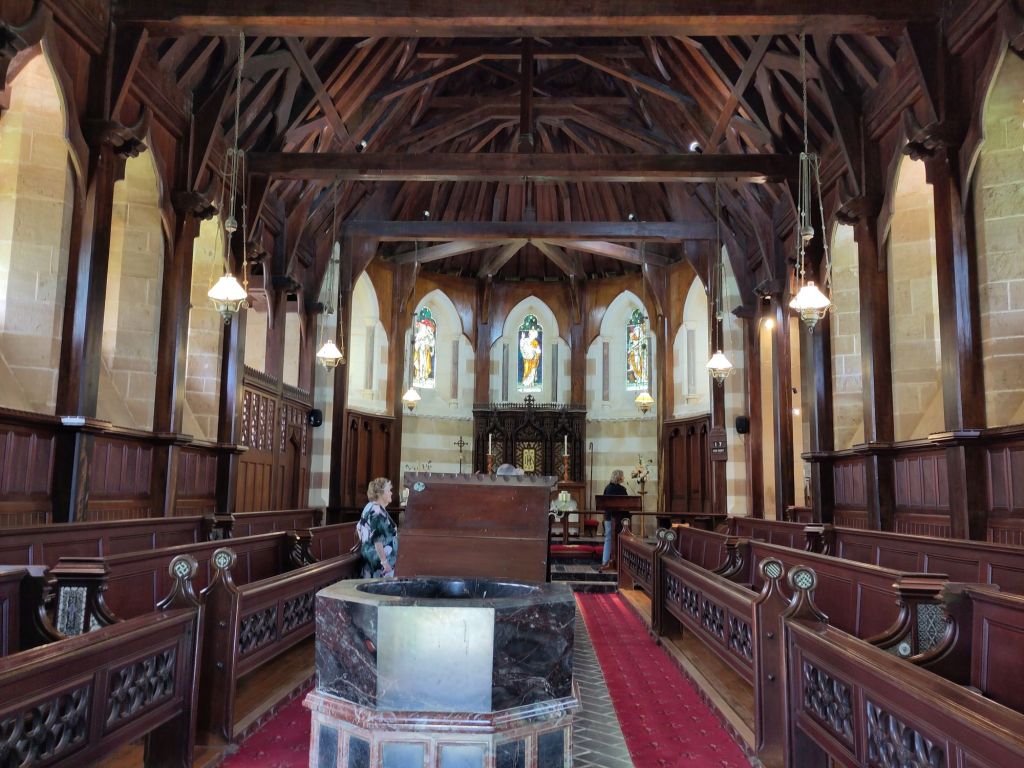

A Melanesian Mission was established on Norfolk in 1866 and ran until 1920. It started with 16 youths from other South Pacific Islands and by 1899 there were 201. The Mission was run by the Church of England where boys and girls were taught about Christianity and general life skills. The beautiful St Barnabas Chapel was built in memory of Bishop Patterson, who was speared to death in a tragic case of mistaken identity.

Modern Norfolk Island

In 1979 an Act of the Australian parliament enabled self-government; the only non-mainland territory with its own legislature. However, by 2015 indebtedness led to a takeover by Canberra and direct administration. The current Norfolk Island Regional Council consists of the Administrator, three elected representatives and three appointed representatives of the Commonwealth and Queensland governments. The Council is very focussed [sic] on economic growth, which is concerning, given the island’s size and its inhabitants’ desire to retain their cultural identity. One wonders where it will lead. The issues are complex and remain contentious and the results of the takeover are a mixed bag. For example, the airport received a major upgrade which has boosted the island’s main economy – tourism – but it’s military grade now and there are differing opinions about who pays for it.

With the introduction of income tax, services such as Medicare, education, the aged pension and policing have been provided. Apparently unemployment benefits have not done the youth much good. Capital works investments are improving Norfolk Islands digital connectivity and sea freight facilities, which may be mixed blessings.

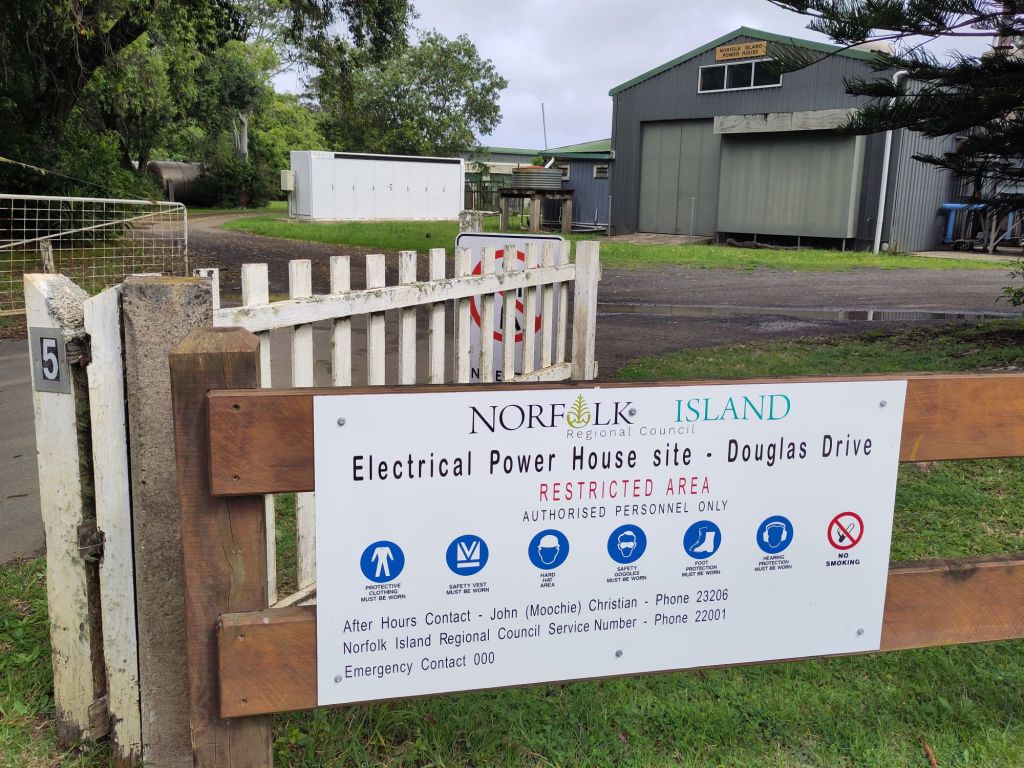

The island’s energy system is transitioning to rooftop solar and battery power which will enable electrification of transport and home appliances. Wind, wave and tidal power were rejected as either unsightly or expensive.

The island is beautifully maintained; cows mow the verges, there is no litter and recycling is now highly advanced. The island has come full circle from a subsistence, low waste economy to abundant, imported consumer goods and dumping everything into a local landfill to a very successful waste management system.

The Economy and the future

I did a Farm Industry Tour and learnt that the island’s industry – apart from tourism – includes exports earnings from the seedling of the Kentia palm (the company is Dutch owned), but quarantine restrictions limit live exports. The Norfolk pine is exported as an ornamental plant and milled locally for building material. There’s also a liqueur factory. Locally, fresh fish is abundant and many people have food gardens which the Pitcairners, at least, share freely among themselves. However, main street sees only a little of this and the supermarket is stocked with a lot of processed and canned food.

The biggest threat to the Islanders’ culture – control over residency – seems to be swamped by other issues. There appears to be no population policy. Immigration has made up for the low birth rate, which has kept the population stable for some time, yet ageing. Recently, property prices have climbed due to investor speculation from overseas. There is less hope of young people staying on the island if they can’t afford to buy a home on local income. Subdivisions would lead to an increase in the number of residents. The island appeals to retirees from Australia and New Zealand. One holds little hope for the continued practice of free burials if there is an influx.

To me there’s a parallel here to Brexit; a failure to distinguish between the issues of immigration and political/economic integration. Norfolk Island, like Britain, might be better off negotiating more control over population rather than extricating itself from the continent. Intentional and sustainable communities have learnt from experience to maintain purpose and harmony, make it “hard to get in, easy to leave”.

Leave a comment