Whatever Happened to Solar Thermal Power Plants?

Sourcing Energy On A Desert Continent That’s Getting Hotter

Renewable energy sources have been getting a bad wrap over the past decade, with the spectacular South Australian state-wide blackout in 2016 highlighting energy security and being unfairly used to scapegoat renewables.

There is political division over where our energy should come from and whether the cost of reducing emissions is an unreasonable burden to householders. Nuclear energy is been touted as a solution, given our vast reserves of uranium, which we gleefully export, without taking back any of the waste.

In the first three months of 2025, renewables (solar and wind) powered 43% of Australia’s electricity grid. Rooftop solar and large-scale solar farms account for 23% and wind, 15-20%. Hydro remains a smaller, though vital part of the mix. Battery storage, although still expensive, is on the rise and fossil fuels will continue a steady decline if current government policy is sustained.

But barely a whisper is heard about solar thermal energy anymore.

Solar Thermal

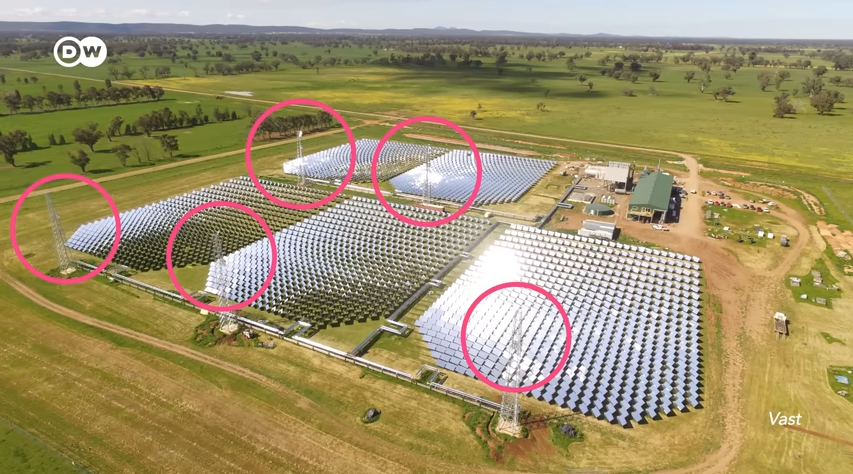

Solar thermal power plants use the sun to heat molten salt that drives steam turbines to create electricity. The advantage they have over photovoltaic panels and wind turbines is that they can provide a steady baseload power on demand overnight or longer. Mirrors (known as heliostats) are directed at a tower to concentrate the sun’s rays, hence the term Concentrated Solar Thermal Power (CST) or [CSP]. Salt is cheaper and more abundant than the materials needed for PVs.

Deserts are ideal for this kind of system and Australia has a lot of them.

You’ve probably seen images of early concentrated solar thermal power plants as vast, science fiction-like structures. One was planned for Port Augusta 15 years ago.

So where are they all? What went wrong?

Most CST plants were built in the deserts of the USA and Spain. The systems proved more complex and expensive to maintain than expected. Keeping so many mirrors angled correctly, clean and functioning was an enormous task. Also, when the central tower had a problem, the whole system shut down. Molten salt is not easy to work with; if the temperature falls, it can turn solid in pipes and prove very difficult to liquefy again.

It wasn’t long before PVs became cheaper than CST. And they were simpler to deal with. They killed CST off.

But CST can do one thing PVs can’t; cheap storage capacity, at least for a few days.

The reality is that for the provision of night time dispatchable energy in the deserts, there’s nothing this cheap.

Craig Wood, CEO of Vast

Vast is a leading company backed by ARENA (Australia Renewable Energy Agency) working on CST Plants with their current one at Port Augusta, SA, another in Forbes, NSW and others overseas. Similar projects are being undertaken in Victoria (Sundrop at Mars, RayGen Solar Power). Vast’s approach to CST utilizes a modular sodium loop system. The modular design consists of several towers, which makes it easier to build. Also, instead of molten salt, liquid sodium (a metal) is used because it’s easier to melt should it cool and become solid.

Sodium sulphur batteries use liquid sodium and sulfur electrodes that can be scalable and store energy for longer. CleanCo is looking at installing one in Ipswich, Queensland and another of these ‘NaS’ batteries has been deployed in Kalgoolie, WA. Japanese and German companies are responsible for the technology.

The Vast Solar Port Augusta CST plant is expected to enter commercial operation in late 2025. The project has a capacity of 30 MW/288 MWh (ARENA).

China is getting into CST big time with 30 projects in development – way more than anywhere else – because the government has specified that every renewable park with 1 GW of capacity must include 10% of storage.

Filling A Niche

It is encouraging to see that through ARENA, the government is supporting CST projects like Vast. However, you would never know it from the news. Talk is mainly about wind and solar PV farms, their problems of intermittency and nuclear power.

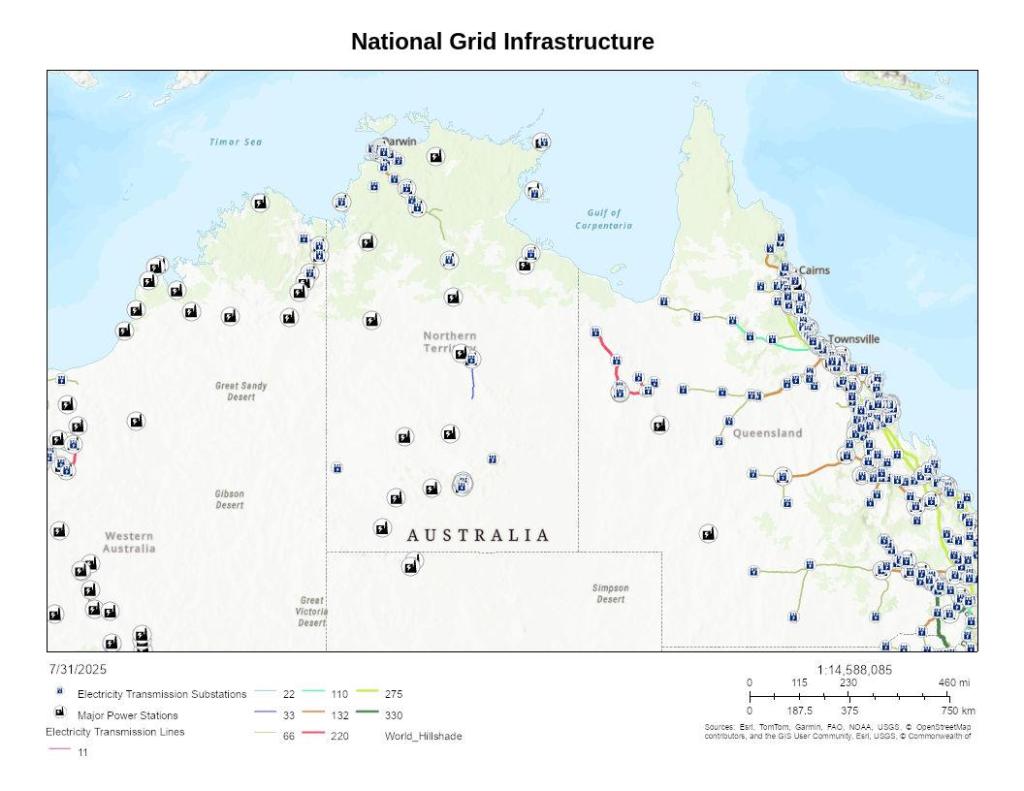

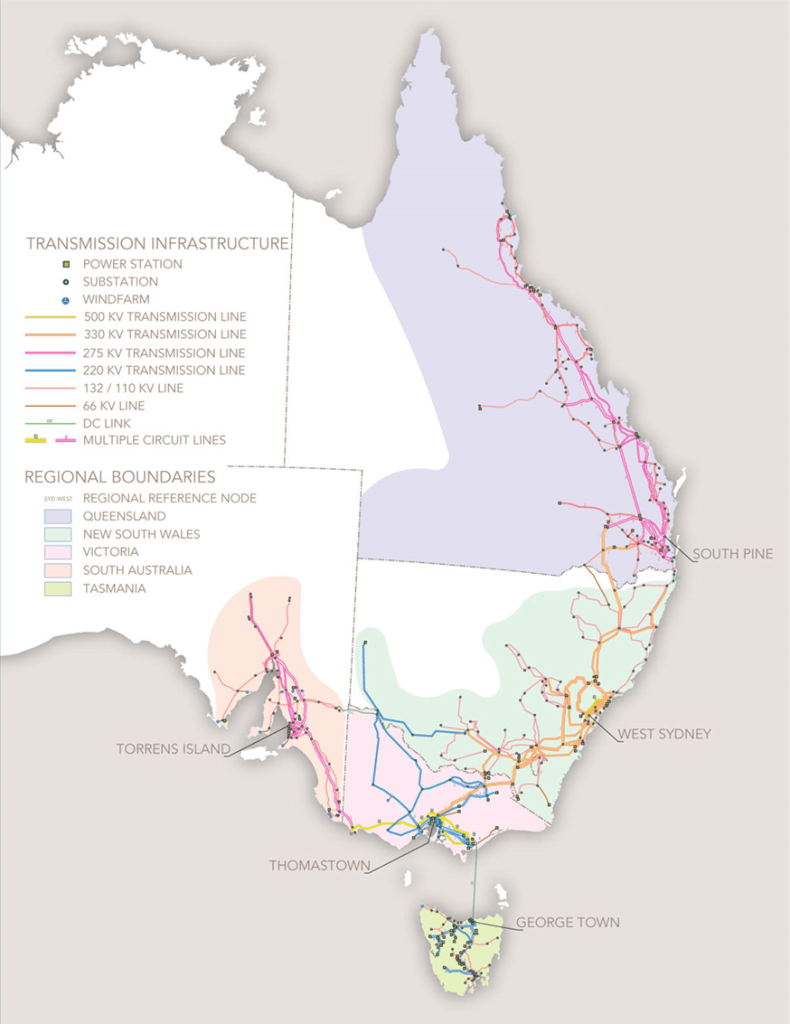

CST is filling a niche in the renewable energy market, but I think it could be a rather significant niche across the many communities that are not part of the national grid system. Most of them are across the north.

The National Electricity Market does not include NT and WA:

The National Electricity Market (NEM) is comprised of five physically connected regions on the east coast of Australia:

AEMC

- Queensland

- New South Wales (which includes the ACT)

- Victoria

- Tasmania

- South Australia

Would small, modular CST power plants suit the outback?

I recently visited Birdsville, south west Queensland, and did some research. It is isolated and relies on PVs, supplemented by diesel and gas generators. Birdsville had a Geothermal power plant that ran, on and off for nearly 45 years. Outback towns like Birdsville are bathed in sunlight all year round, except for cloudy days. The population tends to expand in the 6 months over winter, particularly in a tourist hotspot like Birdsville where thousands gather for the Races and a music fest. This increases demand for power dramatically. Over summer, air conditioning runs non-stop, 24/7. It’s unlikely a single module CST power plant could serve all Birdsville’s requirements year-round without some form of back up. But other towns with more stable populations and demand, might be better candidates. Mt Isa is a micro grid and could be more suitable, even if they were eventually connected to the national grid.

Nuclear and other fossil fuels never have to deal with the weather. That’s hard to beat. But their waste by-products are unavoidable. If the news in the wind is true about nuclear power plants’ waste being recyclable, it could be a game-changer.

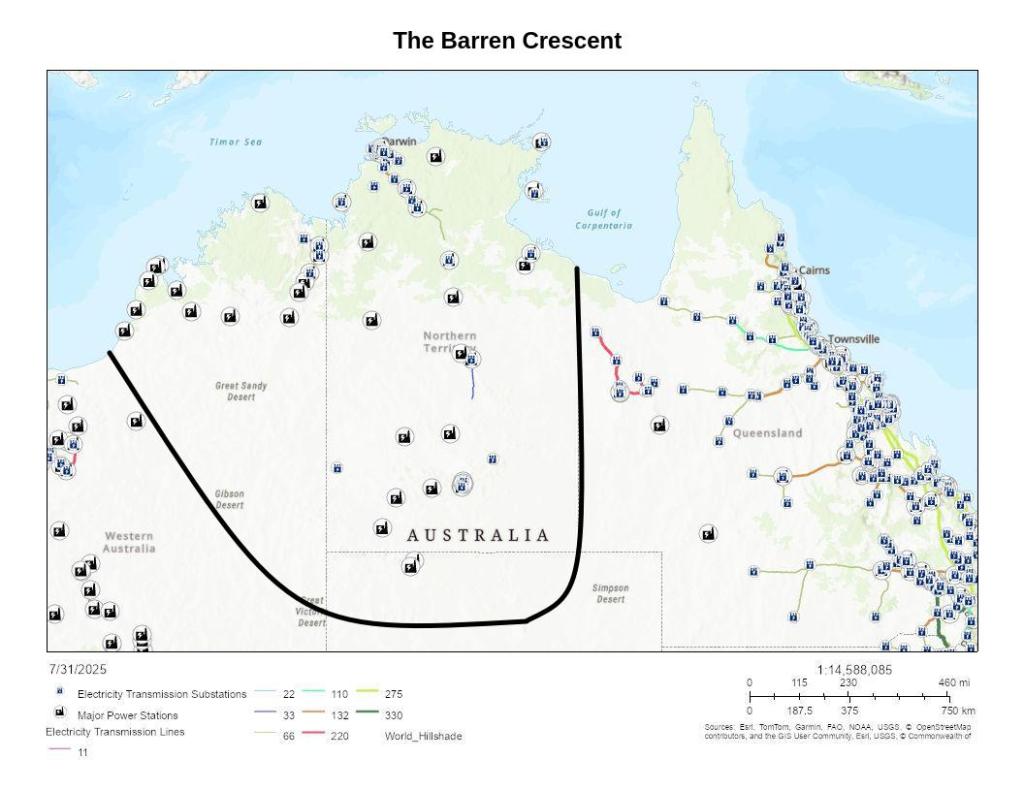

Deserts Abound – Our Barren Crescent

As the climate warms, Australia is getting dryer in the south and wetter in the north. Multiple desal plants servicing our major cities stand testament to the fact we’ve breached the natural hydrological carrying capacity of the southern part of the continent. We pay more for water and it’s less reliable. It’s time we reconsidered what we’re doing, how we’re living and whether we should be looking at the desert differently. Instead of a barren wasteland to be avoided, perhaps it’s a rich source of energy we can adapt to. Coober Pedy in South Australia, with it’s underground homes and opal mines, sets a good example, albeit an exception. We Australians, for all our ‘love of a sunburnt country’, are somewhat averse to deserts. In fact so much so that the barren crescent separating the Northern Territory and the Kimberleys from the rest of the country is one I’ve never heard identified as such. It runs from the Gulf of Carpentaria south along the NT/Qld border, through the Simpson Desert, west across the north of SA (which is SO barren it’s unnamed) then north west across the Gibson and Great Sandy Deserts through the heart of the Pilbara to Eighty Mile Beach south of Broome. This Barren Crescent is a reality that draws a mental block in the Australian consciousness.

The Only Way Out Is In

Too often the answer is mega projects and big tech like the Iron Boomerang Project to connect resource extraction and development supply lines across the north. They have their place, but small-scale projects like Vast’s CST and attention to detail may be easier and more rewarding – especially for ordinary people. What if adapting to our barren continent means using modular CST energy and/or small scale nuclear power plants and living underground, or partly underground to keep cool? Tourism, cattle, resources, energy and IT could provide livelihoods to sustain isolated communities. VAST is also producing renewable methanol, a versatile hydrogen derivative which, if produced using clean energy, has the potential to decarbonise several hard-to-abate industries, including aviation and shipping.

If the Barren Crescent is to be breached, the resources of north Queensland need to be dedicated to the NT, rather than going to the south east. On its own, north Queensland is not viable, but with the NT, it has an adequate tax base to move forward. This is the new northern state I call Capricornia.

The 2021 Australian Infrastructure Plan boasts optimism, innovation and imagination. It is dripping with motherhood statements about growth; growing ‘the economy and jobs’, delivering ‘globally competitive quality of life in Fast-growing Cities by growing economies and populations’. It calls for ‘water security’ for all. In this section is the only reference to climate change in the whole plan and an admission that ‘the security of Australia’s water resources is under increasing threat from climate change, weather extremes, population growth, changing user expectations and ageing infrastructure.’ (page 45). The Plan’s vision of growth is at odds with its tacked-on politically-correct goal of net zero.

In truth the 2021 AI Plan is anything but imaginative. It has nothing to say about the delivery of cross-border infrastructure and state-based funding, other than a dream of ‘national ownership’. There is no indication of a genuine reassessment of development. There is no hint that development could mean reducing demand and doing things differently. There is no suggestion that existing state and territory borders might be hindering one of its central themes; developing the north.

Leave a comment