South Korea, Japan and China Are Involuntarily Slimming Up

But While Their Elites are Resisting It, Ordinary People Are Benefiting

China’s recent fertility rate decline and subsequent population contraction has been getting a lot of attention lately. South Korea has similarly gained a reputation for having the world’s lowest fertility rate. Japan has been living with a below replacement fertility rate for about as long as Australia has; since the 1970s.

There is usually a flurry of catastrophizing that goes around when declining birth rates are announced (The New Yorker). Phrases like ‘we’re an endangered species’ and ‘we’ll disappear’ are trotted out. This is done without reference to overall population trends, productivity or participation rates, quality of life measures or the health of the environment.

The human reproductive instinct is very resilient. Even in low fertility societies, enough people form families and have children to keep numbers falling too far. Let’s take my grandparents’ line as an example, keeping my Australian Anglo-Celtic background in mind. There are ten grandchildren, 11 great grandchildren and five great-great-grandchildren (that I know of) to replace them. Of this progeny, half of us didn’t reproduce. Half, and yet four generations later there’s one extra child to replace the original four parents (and there’s more to come in the fourth generation).

Over those four generations, quality of life has improved immeasurably due to economic growth and a host of other technological and social developments. But the last two generations have been experiencing something of a reversal of that trend. This is true of East Asia, too, albeit concentrated in a more recent, shorter period of time.

Japan’s population is contracting (as is China’s and South Korea’s more recently) and their GDP growth has long been ‘stagnant’. (I parenthesis stagnant for good reason, as I will explain.) Australia’s fertility rate since the 1970s has been only slightly above Japan’s and yet our GDP growth has been significantly higher, due mainly to immigration-driven population growth. But has this been reflected in our quality of life?

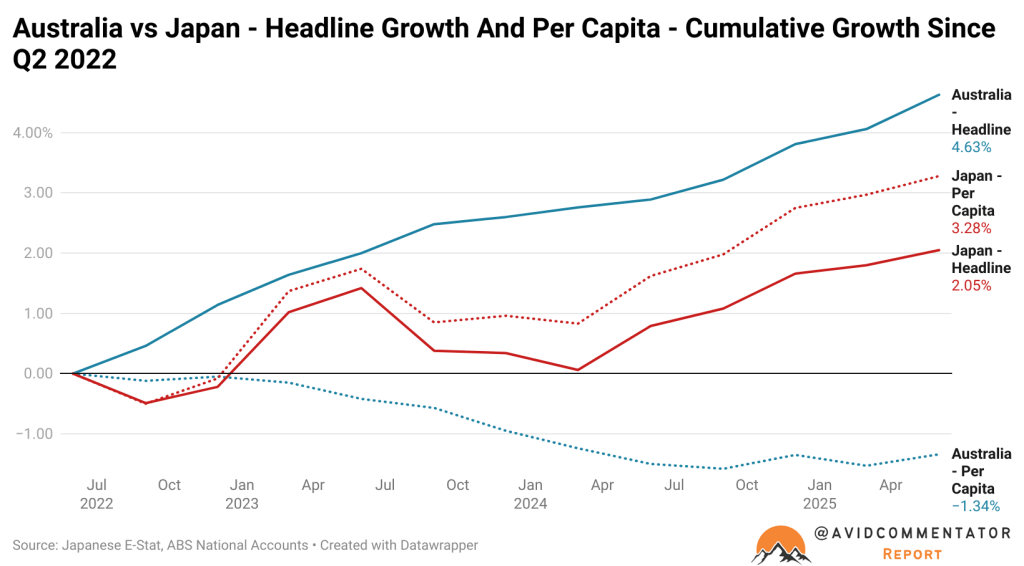

Since Q2, 2022 “Australia’s GDP per capita has contracted by 1.34%, while Japan’s has expanded by 3.28%, an outperformance for the average person in the streets of Japan of 4.62 percentage points”. (Macrobusiness) In the same time, “the Australian economy has grown by 4.63%, and the Japanese economy has grown by 2.05%”.

Australia and Japan are pursuing two distinct economic strategies, with Japan being compelled by its circumstances, while Australia is doing so primarily by choice. In Japan, the contracting population, and in particular the significant ongoing declines in the working-age population, have forced firms to more efficiently deploy the labour force Japan has, improving productivity.

In Japan, the Iron Triangle, which connected the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the bureaucracy and Japan’s corporations in a tightly bonded relationship of mutual self-interest, is coming undone. While the economy was booming, the elites held together tightly. But faced with a new economic reality, there are signs of discord and competition within the elite’s compact. This is typical of a society in a disintegrative phase, as history scientist, Peter Turchin says. However, Japan isn’t unraveling just yet.

Japan’s shrinking population is doing better than Australia’s growing cohort of foreigners. Australia’s lazy choice of rampant immigration has ballooned our population to 27.5 million, the highest growth rate in the OECD.

John Howard fell for the bureaucrats’ mass immigration scheme, led by Abul Risvi (who was Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration and managed Australia’s migration program from 1995 to 2000). Even though Howard felt uncomfortable with the scheme and the colour blind multiculturalism that accompanied it, he went along with it because it sized the nation up and made the rich richer. (Nachman Oz, 2025 Australia’s Rule by Bureaucrat) When Menzies referred to ‘aspiration’, he was talking about making Australians ‘little capitalists’, not billionaire elites. Not only have politicians lost control of immigration, so has the public service. Why?

A debate is developing in Japan about immigration (Is Declinging Population Really a Problem? – ABEMA Prime#アベプラ【公式) . A few years ago, there were signs the elites (represented by the ruling conservative LDP) were trying to sneak immigration rates up without public debate, just like John Howard and the Australian apparatchiks did in the 2000s. With the success this year of the populist Sanseito party and the installation of a hard line conservative Prime Minister in Sanae Takaichi, that idea seems to have been quashed. Just as well.

In China, attempts by the ruling Politburo to reverse fertility decline have fallen rather flat. Young people are sick and tired of being told what to do in a competitive environment that, as in South Korea, makes the future look bleak. There is a healthy counterpoint to this in China, at least, where young people are deserting the big cities and moving to rural towns where property is cheap. There, they’re getting back to basics, setting up BnBs and growing their own food. Meanwhile, the property ponzi economy and wealth pump in Australia continues to discourage family formation.

Getting the balance between high and low fertility is a tricky business. In the 1960s, South Korea understood high fertility to be a retardant to prosperity and had great success through family planning in getting it down. But even after succeeding, the government doubled down and said, “Even two is too many.” Apparently they couldn’t get enough prosperity. Now they’re pumping millions into incentivizing child-bearing. But a culture of intolerance for children has developed. “Last year, strollers for dogs outsold strollers for children.” (The New Yorker, 2024).

Do you see the pattern? The reason clever, sophisticated schemes, politicians and bureaucrats overshoot and undershoot equilibrium is because they’re fixated on materialism – the wealth pump. People are sick and tired of it. They may not know it because they’ve never experienced it, but what we all yearn for is a comfortable life that is spiritually and socially rich in a country with a stable population and a steady state economy

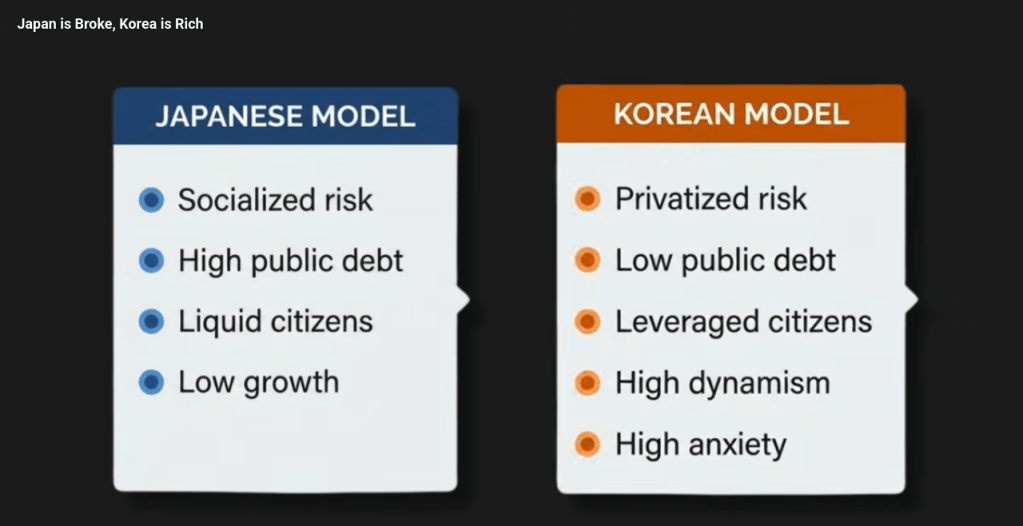

It seems the Japanese have gotten closer to this realization than any other post-industrial country so far. Although Youtube Channel Behind Asia says the price Japan pays is ‘stagnation’, the price Korea is paying is high anxiety.

Japan, it says, has socialized risk with a 235% GDP debt ratio, which it owes to itself. Because the Yen is a sovereign currency, this can go on indefinitely. It has protected its citizens by allowing them to avoid debt and save. The economy isn’t growing but unemployment is very low; 2%. One thing that keeps the economy ticking over is construction – or more precisely, reconstruction; tearing old buildings down that weren’t build to last in the first place, and rebuilding.

Which would you rather be? Stable and happy, or rich and anxious?

Leave a comment