- State Capture

- Plebiscites and Proportional Representation

- Fix The First Flaw – Plebiscites

- Proportional Representation

State Capture

Australia has one of the best governance systems in the world, thanks to our heritage. However, I believe the past two decades of unmandated population growth and growing inequity underscores three fundamental issues facing our democracy.

Australia is a relatively young nation and our constitution has been tested over 125 years. In that time, there have been two gilded ages of rank inequality that has resulted in state capture by elites. We are living through one now. The previous one was in the 1920s and 30s when we were still British subjects and our Federal government was in its infancy. Although we were adversely affected by the Great Depression and World War 1, we were shielded from the worst extremes of that period by the early people’s bank (the Commonwealth Bank), a strong labour union movement, and a very ethnically cohesive society that limited immigration to a carefully selected few. Economic management tools were fewer and more blunt then, so we have since been spared some of the more extreme consequences of downturns.

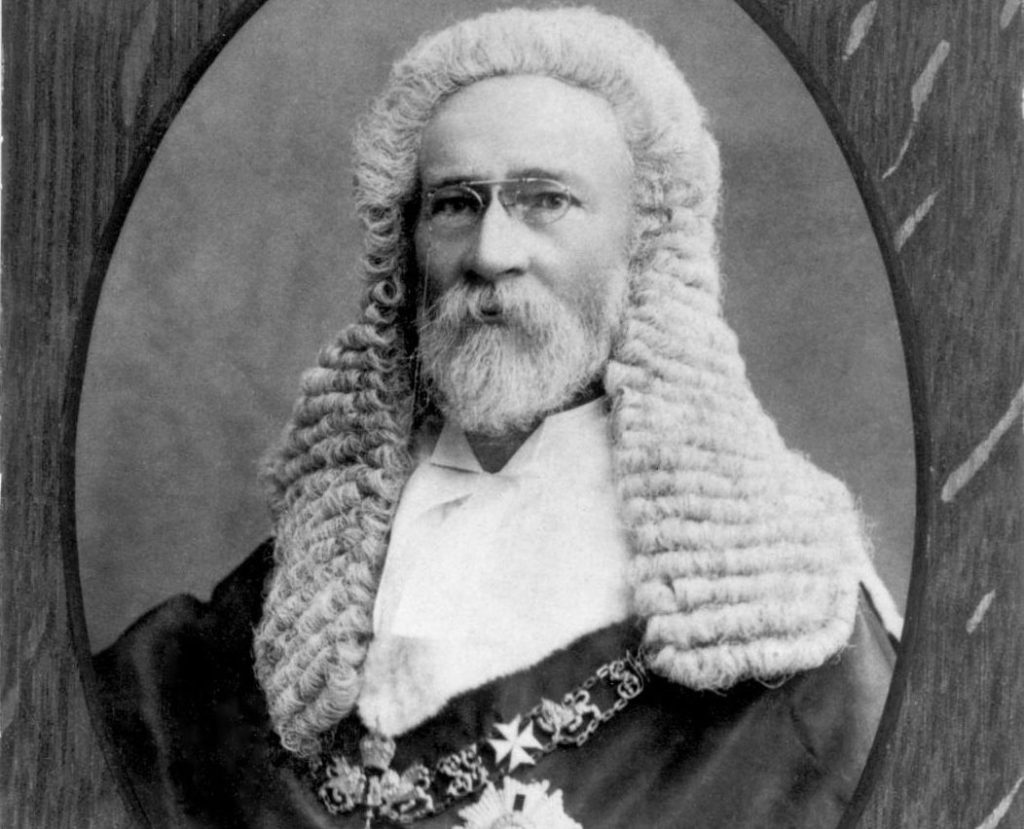

qalbum.archives.qld.gov.au/qsa/portrait-sir-samuel-walker-griffith

However, the past twenty years has seen consequential policies implemented with little to no debate by governments from both sides of the political spectrum on a people who oppose them. It has transformed the country dramatically against the will of the majority. Little wonder first preference votes to the major parties have plummetted.

State Capture is a condition where the political process of a country is beholden to a small, wealthy elite. Political reform is key to rolling back the power of elites because in the past they have been able to skew policies in their favour. Politicians can be captured by lobbyists with leverage (financial influence). Over a period of decades, wealth distribution can expand or contract in waves that can sway members of parliament away from or toward public interests. Politicians can also be captured by ideology. Political and economic theories designed to justify policies initiated by the political and business class can develop a life of their own and the general public are left trying to figure out their response. When a confluence of many complex and challenging changes takes place, the public is understandably flummoxed for a while. It takes time for these theories and ideologies to be implemented and for the public to bear witness to the results before a coherent response is formulated. But not always. Sometimes the public identify the policies very early on as being against their interests.

OFF THE RAILS

Beginning in the 1970s, what Peter Turchin describes as the Great Compression (the period of relatively evenly distributed wealth) began to unravel. In Australia, multiculturalism was ushered in as the antidote to white racism with barely a smidgen of analysis and debate, going from one policy extreme to the other. Feminism and Gay Liberation added to the complex tapestry of issues. These might have been manageable while a single income could support a family and pay off the mortgage. The ’70s was a simple enough time that common sense and intuition told us there could actually be too many people on the planet at once, so draconian policies to reduce births were introduced in India and China. And we also knew that no matter how wonderful nuclear power was, without solving radioactive waste, it was intergenerationally unjustifiable.

But then privatization and globalization was introduced just as the Information Revolution took over our lives. This all worked out very well for the elites, elite wannabes and their minority groupies, but not so much for working families and anyone who grows old.

I vividly recall the month in 1986 when suddenly everything in the news was about the environment. It was almost annoying. It died down, of course, as economic growth regained a foothold and the mantra became ‘sustainable growth’. Global Warming become Climate Change and despite growing scientific evidence, our collective response is very dysfunctional.

Government has been captured by big business and both have gleefully promoted social ideology that seems altruistic, but actually helps their wealth pump. They have found allies in gullible, short-sighted anti-authoritarians who revel in tearing down the nation state and borders. Meanwhile, they’ve also captured the media which keeps up a narrative that what’s in their interests is in everyone’s. For example, inheritance tax is a terrible ‘death’ tax that robs you of the right to pass the fruits of a lifetime of hard work on to your children, when in fact it is designed to only affect the top 2% from maintaining their entitlement to privilege. All this is easier to do when the public is vulnerable and consumed with soul-searching over historical and cultural issues.

I recall back in the early 1990s the then (ALP) Minister for Immigration stated in the media, “There is a perception in the community that immigration is out of control.” That was a good 10 years before the Howard government inaugurated a rise from an annual NOM (net overseas migration) of 80,000 to 250,000 that has been sustained ever since. Except that in 2023, the ALP Federal government oversaw the biggest spike in immigration this country has ever seen – taking us to third world levels of population growth. After leaving politics, Bob Hawke pointed out that there was a silent agreement among the major parties to not discuss high immigration as a policy issue. Even Treasury is on board, advizing governments to keep it up or else GDP could take us into recession (since our manufacturing base is gone.)

The excessive concentration of power in the Prime Minister’s Office is exemplified by it taking us to war in Iraq in 1990 despite widespread protests, setting immigration quotas far higher than have popular support and Scott Morrison’s clandestine accumulation of ministerial portfolios during the Covid pandemic.

BACKLASH

In response to pubic outrage, environment charity Sustainable Population Australia ran a campaign ‘Say NO to a Big Australia’. It has a pragmatic approach to achieving its goals, given the current state of our political process. It aims “to make high migration THE election issue and force a policy shift.”

This is a good strategy for the current political reality – Parliaments are generally responsive to public opinion. But at election time, even a pivotal issue like high migration-driven population growth can be drowned out by a myriad of issues (like housing) that are actually consequent to population growth.

Clearly the concentration of power in parliament is too impervious to pivotal issues.

REIN IN THE RENEGADES

It is time to stop this disconnect now and forever.

The political process is just part of the systemic issues we are facing today, but let us focus on two reforms that would help us get out of this mess.

Plebiscites and Proportional Representation

Sustainable Population Australia is not calling for a plebiscite, because plebiscites are notoriously difficult to initiate. But the unique polling power of a plebiscite is that the question is put to every registered voter and voting is compulsory.

Many people confuse referendums, plebiscites and other forms of polling such as the ABS postal survey on marriage equality. HERE is a quick, clear explanation: How Plebiscites and Referendums Work.

A plebiscite can only be initiated by whoever has a majority in parliament. It is used at the government’s discretion to get unequivocal clarity on the voting public’s view of a particular policy, issue or decision. The government is not bound by law to honor the result, so no plebiscites have been proposed that contain a result the government won’t support. Governments have many ways to gauge public opinion, such as media polls, that doesn’t cost it anything. Therefore, there have only been 3 plebiscites in our 125 year constitutional history and the only one that was successful was the most recent one, in 1977, which offered 4 national anthems to choose from. That’s how we got Advance Australia Fair. This was a far better use of plebiscites than Prime Minister Billy Hughe’s attempts in 1916 and 1917 for the somewhat contentious issue of military conscription.

In its current form, an official plebiscite is a useful tool for a government to farm out the finer, final details of a decision, when it so wishes, to the whole nation. But it doesn’t work the other way around. There is no mechanism for the public to initiate a plebiscite. Plebiscites could and should be an avenue for popular opinion on a particular issue to be brought to bear on a government. In some countries, citizens can initiate a plebiscite with a petition.

Politicians are loath to vote for any limitation to their power, but they have little to fear from this one. It is rare for a large majority outside parliament to form an opinion on something that parliament is either ignoring or at loggerheads with. The public could only mount a challenge to its authority with the support of an enormous, well coordinated and well organized campaign. However, sometimes what is needed is momentum. A mechanism that gives the public the opportunity to get an agenda item on to parliament’s order of business so that the issue is properly addressed would provide the impetus for a campaign.

Prominent constitutional lawyer, George Williams (UNSW) stated, “Plebiscites are rare in Australia. They go against the grain of a system in which we elect parliamentarians to make decisions on our behalf. By contrast, referendums and plebiscites introduce an element of direct democracy that allows people to have a say … they can have a major political impact.” (The Age, 2011)

We need something that goes against the grain.

Fix The First Flaw – Plebiscites

themercury

There is no mention of plebiscites in the constitution. In fact, “A plebiscite is not defined in the Australian Constitution, the Electoral Act or the Referendum Act.” (AEC) Therefore, no referendum to change the constitution is required, unless enshrining it in the constitution is the goal. Referendums are, as Robert Menzies said, ‘a herculean task’.

Legislation can be introduced in parliament that beefs up the role of a plebiscite. Naturally this requires parliament to give up some of its power. While this is a tall order, it is not quite as herculean as enshrining it in the constitution.

The legislation should enact a law to enable a certain (significant) number of citizen signatories on a petition to initiate the introduction of a Bill to parliament requiring it to instruct the Electoral Commission to hold a plebiscite on a particular policy issue. Parliament’s power to influence the Bill is a matter for constitutional lawyers, but may include the power to alter the wording (not the substance) of the question, the power to vote the Bill down and whether or not it needs to be approved by both Houses. In the latter case MPs would be accountable for their actions when the next general election was held. If the plebiscite is held, a simple majority (or more) of the national electorate would be required for the question to succeed. (The action could be specified in the plebiscite, such as introducing a particular Bill to parliament to legislate on the policy in question.)

The result should be binding on the government of the day. Remember, plebiscites cannot change the constitution, they are designed for individual policy issues such as conscription, the national anthem, the national flag, population policy and involvement in a foreign war. In practice, this would take little power from parliament, but it would enable the voting public to highlight an issue it feels is being ignored.

This is one safeguard against state capture.

Proportional Representation

Currently, support for the two-party system, or ‘majoritarian’ government, is breaking down. First preference votes have fallen to the 30% range, creating a 30/30/40% breakdown. The cross bench has expanded and minor parties are seeing more success. However, the allocation of seats in the lower house (the House of Representatives) does not in any way reflect voting patterns. In 2022 the ALP, romped into government with a comfortable majority of 52% of the seats on only 33.2% of the popular vote. In Britain it’s worse, with the Labour Party winning an even bigger percentage of seats at the 2024 election (and they’re stuck with that for 5 years!).

The extent to which party policies have become uncoupled from public opinion, as described above, illustrates how unrepresentative our electoral system is.

Minor parties and independents often aim for the Senate first – it’s easier to win a seat in it because it is proportionally represented. It’s not perfect, but of the 76 seats, the ALP has 32% (25 seats), the Coalition has 40% (30) and the cross bench has 28% (21). Much closer to their actual support from voters. The Senate acts as a check on the power of the House of Representatives.

The cross bench – independents and minor parties – are likely to gain from electoral reform introducing proportional representation and therefore will support it. With a growing number of minor parties and independents gaining ground and yet still sidelined by the two major party electoral system, the potential for change is in the wind.

The major parties argue that the current system in the lower house, which favours the front-runner, delivers us stable government. In fact, it’s a kind of gerrymander. It tends to herd people into one of two antagonistic parties and their ideologies. It stifles free thought. It fosters aggression and assertiveness over negotiation and compromise. The two party system bakes an adversarial culture into politics. The opposing sides are always at loggerheads with each other. Except when they have a common interest, such as bolstering their advantage.

HOW TO CHANGE IT

The House of Representatives’ electoral system is broadly described in the constitution and it does not proscribe proportional representation. Therefore, we do not need a referendum to create a proportional representation system. Section 29 (Electoral Divisions) of the Commonwealth Constitution states that each state has the power to implement electoral systems “until the Parliament of the Commonwealth otherwise provides”. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 meant State electoral laws ceased to have effect for the Federal Parliament:

This legislation [Electoral Act 1902] and subsequent amendments were consolidated in 1918 and formed the basis of the Commonwealth’s electoral law. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 has been substantially amended over the years.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act

More recently, minor changes to the Electoral Act affecting the Senate occurred after The Dismissal in 1975 and after the minor party preference distribution deals in 2013 that saw the Australian Motoring Enthusiasts Party Ricky Muir win a seat in the Senate.

The most recent ‘reform’ is the Electoral Reform Bill 2024 that Labor and the Coalition rushed through the lower House without review by a multi-party committee lowers the cap on political donations to parties from private donors and on their spending but severely cuts donations to individuals, effectively killing of funding for Independents. It’s worse than that, however according to the Australia Institute. It raises public funding for existing parties’ campaigns and the donation caps are not as limiting as they seem. More taxpayer money could be paying for party campaigns than before. The ‘reform’ entrenches the advantages the exiting parties have. The Bill is before the Senate at the time of writing and comes into effect after this year’s election (ABC).

The two leading advocacy websites linked here (PRSA and ECANZ) do not indicate how to achieve proportional representation in the House of Representatives. PRSA’s proposal is designed to comply with the constitution (and it also calls for entrenchment in the constitution).

Proportional representation is practiced in Tasmania, the ACT, New Zealand and most European countries. In Britain, Reform UK has adopted electoral change in its policy platform.

Changing the dynamics of power in parliament requires a huge groundswell of public support, something that multiculturalism has made more difficult to achieve on virtually everything. But that is another story. A Bill for reform that removes the major parties’ advantage is unlikely unless the crossbench is large enough and major party MPs are willing to cross the floor.

Until these reforms take place, many voters will continue to have no one to vote for because no one is representing their views. Under these circumstances, I recommend voting strategically, in order to put members of parliament on as slim a margin as possible and create minority governments. This is the only way to make parliament more accountable to constituents under the current system. It will also nudge us closer to a multi-party system.

GETTING THE ELITES ON SIDE

Australian elites are, for the most part, disinclined to philanthropy, according to Dick Smith. Most of them seem to be corrupt in one form or another and although many are ignorant, I’d say they’re blinkered, not stupid. But not all of them deserve to be written off. One super wealthy group in the United States calls itself Patriotic Millionaires. This is a small minority of rich people who show some sign of integrity. In their letter Proud to Pay More, they have been asking the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland, to tax extreme wealth for several years (ABC). I first became aware of this listening to Nick Hanauer’s TEDTalk Beware Fellow Plutocrats: The Pitchforks Are Coming. If we tar all elites with the same brush, we will overlook some important ones and miss an opportunity to support their attempts to influence their more nefarious colleagues.

Impossible, you say? Maybe, but it has happened before. Medieval Debt Jubilees occurred numerous times to reboot economies that were strangled by gold coinage concentrating into too few hands. In the early 20th Century, a small group of elites convinced the rest of their privileged clan that it was in their interest to spread the wealth around to avoid what they all feared – a communist revolution (Peter Turchin). During the Great Compression, the highest income tax bracket in the United States went up to a staggering 90%. Those were the glory days of America’s mid century Nordic model economy. This was achieved because the elites agreed to shut down – or at least slow down – the wealth pump. It was a deliberate strategy to preserve their privileged position by sacrificing some of it. It seems very unfamiliar and unlikely in today’s complex globalized economy. But the Great Compression was unprecedented in size and scope. It spanned the Western world, because of course elites are truly international and know no borders.

Today, as was the case then, for a minority of insightful (even alturistic?) elites to succeed, there needs to be sufficient worry about impending doom for them to be motivated to act against their immediate wealth-hoarding interests. The ‘collapse that is now so powerfully indicated’ may be just the thing to do it. Tech billionaires are taking it seriously.

In Australia, what is needed is someone to bring the philanthropically-minded elites together in the same room and talk about collective action. People like Dick Smith, Matt Barrie, Bruce Buchanan and Alan Kohler.

We will never get rid of elites entirely. So, to ignore them or pit ourselves against them and attempt to overthrow them is futile, even infantile. Like it or not, we have to pick the best of them and throw our support behind them.

Leave a comment