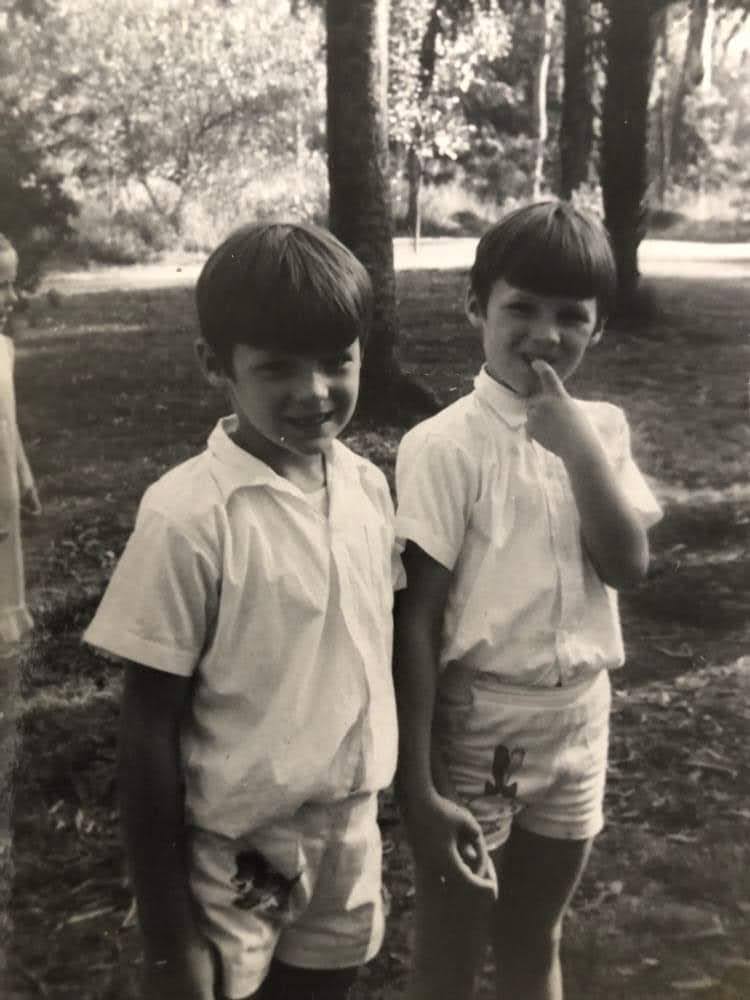

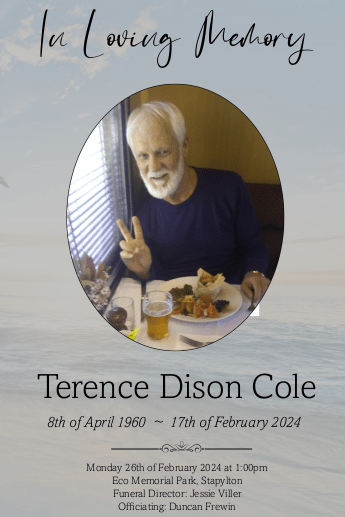

April, 1960. Terence Dison Cole was born around 9am, 10 minutes before me. My twin paved the way with his head and I followed breach-birth-style. He was little a bigger than me, too, and it wasn’t long before his confidence and daring shone through, especially at junior school athletics.

Despite our identical genes, there were differences. These differences set our lives on very divergent trajectories. But for the time being we were inseparable. It’s hard to describe what it’s like to be so connected to another human being.

He was the sombre, serious one and I was the whimsical, giggly one. When our adolescent hormones kicked in, he became more physically daring and socially confident, whereas I felt more and more vulnerable. One Christmas after Mum’s first divorce and there was (once again) no adult male in the house, she came home with a gift for the three of us. To our older sister (by 18 months) she gave something all 9 year old girls would like – probably a pretty dress, I don’t remember. To my brother she gave a toy carpentry tool kit and to me a Golly Wog doll almost as tall as I. Terry burst into tears. At the time we didn’t know why, but it was because the gifts catalyzed the feeling that he was alone in the family, or fatherless.

Dad had died of leukaemia soon after our first birthday. From all reports, he was almost too good to be true. A handsome, young, well-spoken, educated and meticulously-presented English gentleman. Everyone like him. Mum adored him. Family friends helped prepare for life after his passing by turning the family home into dual occupancy, for more income. However, Mum had already forged a professional career in psychology as a tutor at Melbourne University. She was intelligent, vivacious and emotionally flawed. Her mother had told her that she had tried to abort her. As an unwanted child, she struggled with fears of abandonment and losing her husband was devastating. In grief, alone with 3 infants to raise, it all became too much. She had to get away and went to Singapore for a month, leaving us in a child care centre. When she returned, she said we cowered under a bed and wouldn’t come out.

Terry warmed to our first step-father. He had three grown children, so it was the Brady Bunch except for the 10 year difference with our step-sibings. He took us to Baghdad for two years where he worked with the United Nations installing a telecommunications system. However, by the time we returned, the marriage was on the rocks. There were fights and a lot of acrimony. By 6, we were fatherless again. The experience embittered our mother and her brittle pride turned into female chauvinism. “All men are bastards”, she would say. This, and other inappropriate behaviour, was deeply offensive to Terry.

However, at 43, Mum wasn’t content being single. She dated Rear Admiral Brian Murray who later became the Governor of Victoria. He too had 3 children our age. We all got along very well and it seemed like we’d become a happy Brady Bunch for real. At last, everything was going to be aright. Everything was going to fall into place. But Mum felt she was too unconventional to conform to the expectations of a Governor’s wife; giving speeches and cutting ribbons. He later married an ex-nun.

This was a hugely missed opportunity for Terry as well. He would have thrived in a traditional family. Instead, he had the misfortune of being the only heterosexual male in an intolerant matriarchy. I sometimes suspect his life-long reluctance to accept my homosexuality came more from an irrational sense of betrayal than any sort of moral objection.

People can’t help themselves. Sometimes the odds are insurmountable. Sigmund Freud claimed he discovered the “Third Great Humiliation of Man” – that we are not in control of our minds. I can attest to that, having lost mine at age 21. I spent 6 months in psychiatric care. I wasn’t medicated, though – it was purely environmentally-induced confusion. However, we do have the power to influence our minds and Buddhism gives us practical methods. Terry and I both dabbled in multiple religions. After a brief upbringing in the Anglican Church that included 6 months at Sunday school – my primary memory of being Christian – Mum took us out of it because it ‘disapproved of her divorce’. We were then cocooned in her religious world-view, which was a very individualistic take on New Age spiritualism. It was open-minded, inquisitive and based on her experience of ‘the other side’. She would talk of her ‘guides’. Much later, she introduced me to the Theosophical Society that her beloved maternal grandmother had been a member of. It is a matrilineal tradition I’m proud of. This was all very well, but Mum was incredibly emotionally insecure with opposing views. As Terry and I grew up and developed minds of our own – or tried to – the home environment became increasingly crushing. Sunday school was eventually replaced by weekends at Pony Club, which was probably a life-saver for me, had it not led to tragedy for Terry. Weekdays at school were completely different – all the complications of being oppressed at home were playing out in our relations with our peers.

Then our second step-father appeared. But he was only 9 years our senior and 25 years Mum’s junior. Not really a father figure. Despite his intelligence, cultural literacy and creativity, he was emotionally ignorant and vain.

Then came the big turning point in Terry’s life. While horse-riding, he raced to make a jump with a friend. His horse stumbled and rolled over in a cloud of dust. I saw it from a distance and knew immediately something terrible had happened. I raced down the hill to find him a twisted and seemingly mangled, motionless heap on the ground, out cold. I could feel our father’s presence as I burst into tears and wailed beside him for an hour. It was May 22nd, the same day Dad had died.

By the way, the word ‘Dad’, wasn’t part of my vocabulary growing up, any more than ‘father’, ‘Papa’, ‘Pops’, ‘Daddy’ or ‘the Old Man’ were. My sister, brother and I didn’t start referring to our father as ‘Dad’ until adulthood.

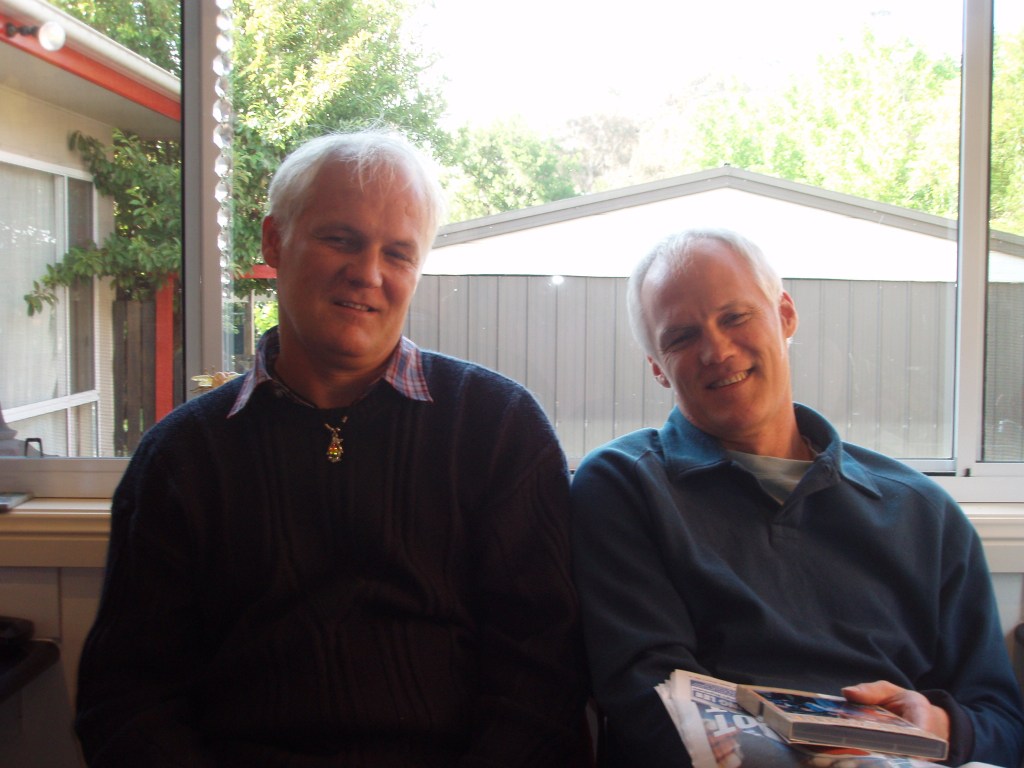

Terence was never the same. He was in a coma for a month and spent 12 months recovering the use of the left side of his body. His personality changed. He became introspective, philosophical and much less daring. Up until his accident, I had felt he was the strong one and I was vulnerable. After the accident, the tables turned and I had to be strong. The connection between us broke and I felt we were more like fraternal twins or just brothers. So, I lost him then – partially. This is the second time I’ve lost him and of course, the final loss. I’m pretty sure if I hadn’t lost him the first time, this time would be much harder.

We were 12 years old then.

Terry told me he considered committing suicide when we were 14 years old. At 17 he was diagnosed with scoliosis. This didn’t seem to surprise or disappoint him. He never regained his optimism. I asked myself – and him – why he didn’t take better care of himself. Although he never smoked, drank or did drugs, one time I visited him, he was driving a clapped-out car (as usual) with an exhaust manifold that was leaking fumes into the cabin. His weight fluctuated significantly, sometimes. He would even chide me for standing up straight.

We graduated from high school and both took off on a bus tour around the country. We went our separate ways before returning at the start of the university academic year.

Terry and I had learnt to play the piano in high school. We continued musical pursuits albeit in different styles; I relied on sheet music, but Terry took to improvising and composing his own songs. I was impressed with this flair he had for creativity. We both went to La Trobe University. He entered the Music department and I entered the Behavioural Science department. He later completed a Music Business Management course in 1993.

He dabbled in other artistic pursuits – paintings and animations.

He was a clever wordsmith and completed a Diploma of Arts in Professional Writing and Editing at the Gordon Institute in 1999 while living in Sydney. Sometimes he really hit the nail on the head. He gave me the nickname ‘Mellowcotton’ which he suggested for my email account and which I chose as my Radical Faerie name. I suppose he saw me as soft, woolly and white. But it was very apt. I had spent 13 years living and working in Japan where they sometimes say they are like ‘peaches’ because they’re soft on the outside, but hard on the inside. ‘Mellowcotton’ is the Spanish word for ‘peach’.

When asked in his Power of Attorney document what was most important to him, he wrote “his travels”. In the mid-1980s, he sort of followed my lead and backpacked through India (where he saw Halley’s Comet), England (where we met at our Uncle’s and then went to The Netherlands together) and Europe (where he ventured off on his own, wishing I had continued with him). He went to Denmark, Germany, and Austria. He met a fella who drove him through Yugoslavia to Istanbul and Gallipoli, then to Athens.

On his way back home, he stopped and stayed in Thailand, which began a life-long association with that country.

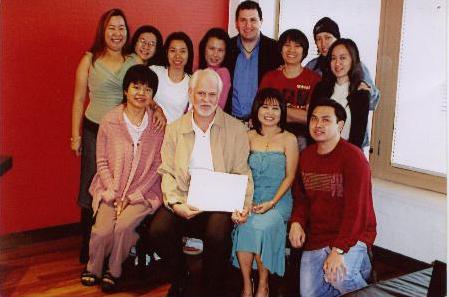

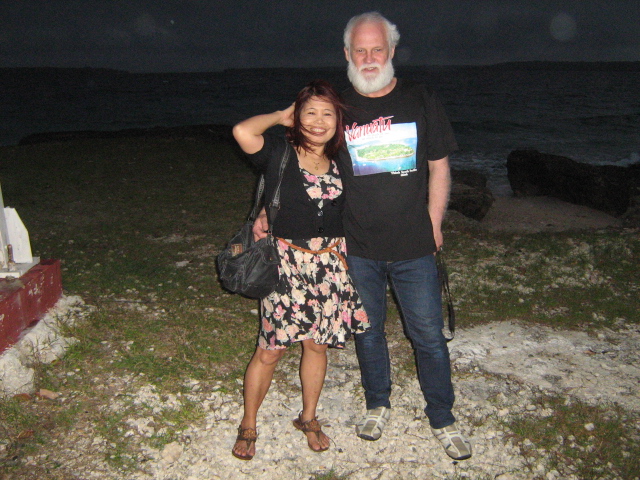

He lived there and married in 1990, visiting me in Adelaide briefly with his family. Upon returning to Thailand, he divorced but continued living there for a while with another beau whom I know he was very much in love with, until finally returning – alone – permanently to Australia in 1993. He settled in Sydney where he busked with a guitar on the streets, playing his own compositions for several years and pursuing other creative interests. He married Saifon Bunmakiang in May, 2005. They remain close to the end.

Later in life he did a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. He had become a devout Muslim. He studied in mosques in Brisbane and learnt Koranic verses in Arabic, which he could recite from memory. His association with Islam lasted more than a decade, however, he recently confessed to me that all he had really wanted was friends. Ultimately, he became agnostic.

At one point he became fascinated by an Englishman called Timor Joe. Timor Joe somehow became stranded on one of the Timorese islands in the late 1800s. He suffered terribly at the hands of the natives who enslaved him and on one occasion tied him to a tree and let wild hogs maul his genitals. Timor Joe was rescued by a British vessel and he ended up in Williamstown, Victoria, where he lived out the remainder of his years. Terence researched his life and this culminated in a presentation to the Williamstown Historical Society.

In preparing this Eulogy, I read some of Terence’s memoirs and correspondence that I found with his Will. In his memoirs, he wrote about the importance of creativity. He wrote a sort of poem that goes;

I always had a dream of leading a band

A band that plays in Synchronicity

With All We See

He invented a dance he called the “Nuclear Shuffle”. He demonstrated it to some female friends who, he said, refused to believe it was his own work.

He also wrote of searching for love and affection with women. Both of us, like most people, have yearned for intimacy and companionship. However, I have wondered whether the experience of coming into the world as identical twins, who are then separated, left us both with a deep-seated need to recapture that intimacy, perhaps more than most people.

In a letter that he had kept, he wrote:

To my mother – my best companion – whom I love and respect and sometimes do not, for lack of wisdom.

Terence Cole

Who we are is preordained. I believe we must strive to be who we are meant to be. Our society tells us we can strive to be who we want to be in spite of our destiny, but [I think] it will be to our detriment, in the end. We may be happy, or think we are happy being whoever we want to be with intelligently construed ideologies to back us up. The less selfish path leads us in the direction of constantly seeking better ways to show we appreciate what we have been given.

Three years after our mother died at 93, Terry receved a diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. He was 59. The prognosis was 3-5 years.

I spent the following 4 years encouraging him to make the most of the time he had left. We ticked some things off a bucket list, but he was engrossed in the struggle and COVID put a lid on it, too.

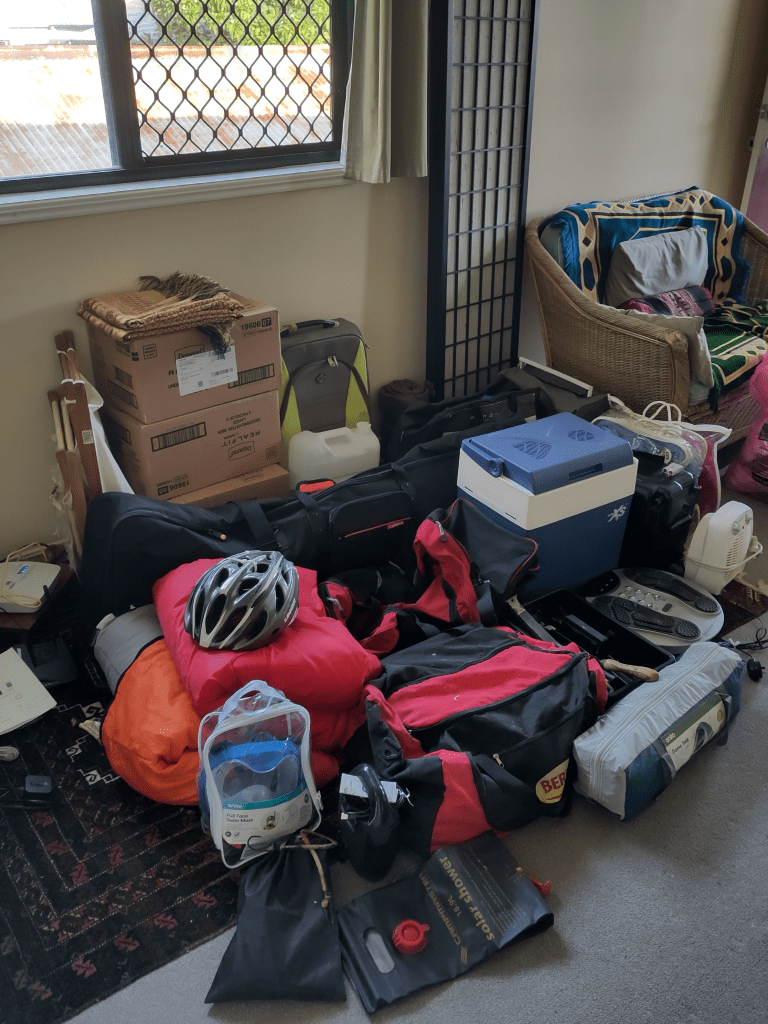

Death isn’t all bad. We tend to catastrophize it. However, one less person means there’s more to go around for those who are left behind. Instead of taking Terence’s belongings to the tip, I’m going through it all carefully, valuing it, cleaning and checking things work and giving away things to needy people or, selling them cheaply. I’m stocking up on consumables. I’ll have enough toiletries for 2 years! I’ll enough shoes for 15 years. I feel this is more respectful, appreciative and sustainable.

Terence became more peaceful in his last few months. Fon (Saifon) said he said he was happy and didn’t want to die. I made sure he heard the words he had asked his Power of Attorney to utter; “Let the struggle go! The Power is out there!” They were very apt for him at that time. His last few days… in hospital… seemed a sort of reckless, happy careering toward the end. He was flirting with the nurses. He said that he had asked a nurse called Meredith for a kiss, so he would have a ‘merry death’. He joked that he was entering his second childhood and among his last words were the nursery rhyme, “This little piggy went to market. This little piggy stayed home.”

The relationship between men and women was a central paradox and conundrum to Terry. I can’t think of a better metaphor for him than something attributed to Henry Kissinger, who wisely joked that “Nobody will ever win the Battle between the Sexes – there’s too much fraternizing with the Enemy”.

An abbreviated version of this obituary appears in the Cleveland News

Leave a reply to Cathy Stubbs Cancel reply